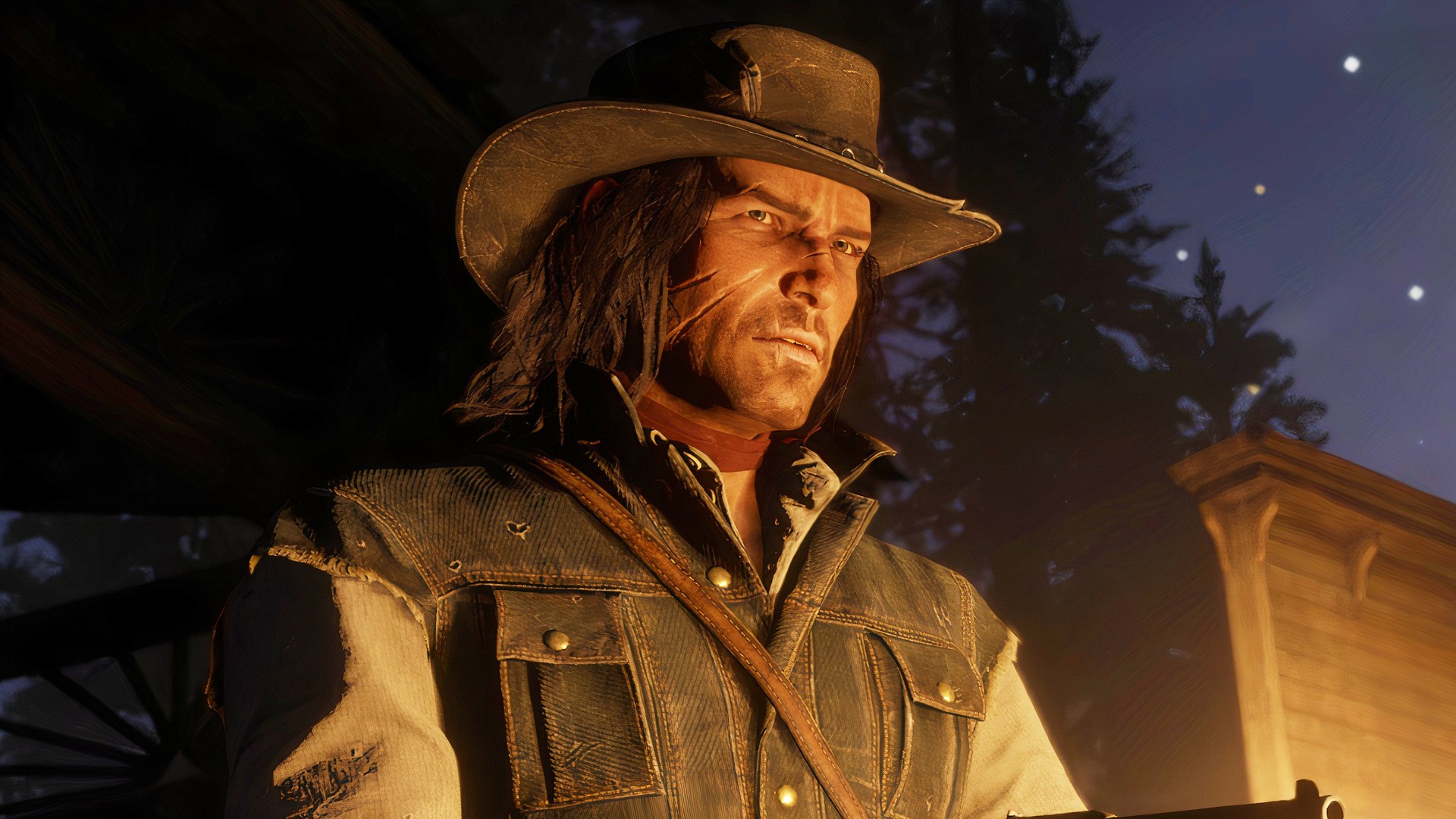

Name of Obligation, Purple Useless Redemption 2, Far Cry, GTA, and numerous different taking pictures video games battle to inform coherent tales. This isn’t to say these video games are dangerous, or that they don’t have their very own, numerous, narrative qualities – RDR 2 and GTA 4 particularly are very competently written. However all of those shooters have the cohesion and efficiency of their drama nearly terminally undermined by the identical problem – one which traditional Christmas movie Die Onerous neatly illustrates.

I’m going to make use of Purple Useless Redemption 2 because the premier instance right here, as a result of it’s a well-written motion journey recreation, the characters are convincing, and it’s broadly thought to be being surprisingly, nearly groundbreakingly cohesive for an open-world shooter. RDR2 is, briefly, probably the greatest examples of narrative and drama in large-budget videogames, and even it – for all of the superlatives you may apply – is nearly undone by this persistent, borderline-fatal flaw shared by trendy taking pictures video games.

Arthur Morgan is a cowboy with a conscience. Significantly as RDR 2 progresses, he turns into more and more delicate to the struggles of John, Abigail, and Jack, and, correlatively, extra disturbed by the worsening violence from Dutch, Micah, and the remainder of the gang’s extra mercenary members. He’s – by the sport’s quasi climax – a weak character whose destiny appears to hold perpetually within the stability.

The threats of seize and impending dying, and the necessity to change into a greater particular person, inspire him all through his private closing act. Likewise, the Van der Linde gang itself is described as always precarious, narrowly avoiding apprehension from native sheriffs and Pinkerton detectives, and desperately attempting to take care of a low profile ample that they will accrue sufficient cash to flee civilisation.

Like coal turning to a diamond, Arthur Morgan and Purple Useless 2’s story develops and improves owing to the fixed software of strain: if Arthur and the gang are to get what they need and doubtlessly inaugurate a greater life for themselves, they first need to survive.

All of which – dramatically, narratively, thematically – is near obliterated by the truth that Arthur, at any given level, can effortlessly and with out consequence gun down actually lots of of armed opponents, be they members of the regulation, rival bandits, and even educated troopers.

We kill, and kill, and kill in Purple Useless Redemption 2. As critics and gamers, we’ve already argued concerning the ethics of presenting violence as blasé, however what’s much less mentioned is how the stratospheric bodycount in Purple Useless Redemption 2, or any of the opposite video games talked about on this article, successfully robs shooters of dramatic efficiency – how each concern, problem, or impediment a personality could face, emotional or in any other case, turns into considerably more durable to take severely once they, canonically, are capable of swiftly (typically stylishly) overpower anybody which may trigger them hurt.

When Arthur Morgan single-handedly dispatches 40 or 50 or 60 Saint Denis officers, his later conversations with Dutch, about how the gang has to maintain a low profile and is liable to being killed by the pursuing regulation, change into very onerous to take severely. By affiliation, the story of the deteriorating dynamic between Dutch and Arthur, whereby Arthur begins to view his long-time mentor as more and more unhinged and disturbingly keen to place the remainder of the camp in danger with a purpose to fulfill his personal regal ambitions, loses credibility and dramatic weight.

Additionally, if Arthur can homicide, seemingly, anyone who may confront him, in any quantity, how may something Dutch does actually put Arthur or his associates in danger, and why would he be nervous about that? FPS video games like Name of Obligation, Far Cry, and different gun-toting video games like GTA – if one of many fundamental catalysts for melodrama is risk, or not less than a fundamental sense of contest or confrontation, video games the place it’s eminently doable to get away with killing everybody arguably sacrifice that exact narrative elementary.

Which isn’t to say there isn’t worth or value in video games the place you kill with absolute energy and impunity. The story of Doom, a lot as its persistent sense of the Doom Slayer’s invulnerability and righteousness of his battle towards Hell ratified by each mechanic and design alternative will be known as a narrative, works exactly due to the lethality and sturdiness supplied each to the character and the participant – Doom is enjoyable, and dramatically satisfying and rewarding, for the actual fact you may kill and survive something.

Not each shooter falls sufferer to the identical problem, whereby the protagonist’s unassailable talent with a gun renders them proof against the risk, and within the course of neutralises the drama. Quite the opposite, the dramatic potential and cohesion of some shooters depend on, and are made extra gratifying by, the characters’ superlative skill – and never simply with Doom, however Halo, Gears of Conflict, and Max Payne.

Nevertheless, within the case of video games the place vulnerability, hazard, and a way of being the underdog are important to the plausibility of the plot – the place, with a purpose to be thrilled by our hero’s journey, we should additionally consider that they’re someway towards the percentages and surviving however solely precariously – I’d flip to Die Onerous, unquestionably the best Christmas movie, to function mannequin.

Considered one of Die Onerous’s biggest qualities is the effectivity and readability with which it establishes stakes. We’re reminded, at a number of interludes, exactly what number of terrorists confront John McLane: 12, or 13 in the event you rely the peevish hacker Theo. Equally, the movie reinstates, at each alternative, John’s susceptibility and reception of harm.

He has no sneakers. He begins the movie with a handgun solely. Crawling by a vent makes him soiled. Strolling over glass makes him bleed. Within the film’s climax, when he lastly involves kill Hans Gruber, who has taken John’s spouse, Holly, hostage, she takes one take a look at John, limping, bleeding, shot within the shoulder, and remarks merely: “Jesus.” It is a hero who sweets, bleeds, and will at any level get killed.

Confronted with tangibly insurmountable odds – 12 on one – his battle, his narrative, turns into extra compelling because it comes at the price of his physique. He’s, to the extent that an motion hero carried out by Hollywood star Bruce Willis will be, a human, one thing we recognise if not by his worry, his indelicate language, and his determined improvisation all through the movie, then not less than by his breakable anatomy.

McLane’s story, then, turns into one to which we are able to extra simply relate. Simply as now we have our personal human dramas, intimately understood to ourselves, John’s passion is obvious and immediately understandable to us as tough and unfair: on their own, he should kill 12 males.

The impact of that, of perceiving and empathising with the momentousness of what John should overcome, is compounded by our recognising him as an individual. Like us, he has limits, made metaphor in Die Onerous by his sluggish, bodily degradation. Like us, he has to take care of unjust and brutal circumstances.

It is a story we are able to get behind, which in flip makes each flourish of violence and spectacle all of the extra gratifying. When John McClane succeeds in killing somebody, it means one thing to him – 11 now, down from 12, and nearer to survival. And since John is noticeably an individual, one in every of us, that victory and all of the feelings and inside drama that attend it, is transferred over to us.

Quite the opposite, if we are able to kill and kill and kill, as is sample in shooters, any try made by the sport to humanise or current as weak our protagonist turns into a lot more durable to consider, with the cohesion of the sport general struggling as consequence.

Arthur Morgan sweats, swears, drinks. He makes terrible errors, and, like John McClane, is proven to have a human physique, inclined in his case to tuberculosis. To an extent it really works: he’s nonetheless probably the most empathetic and recognisably humane characters in in style, big-budget video games. However whilst he’s allegedly within the closing days of life, weakened and moldered by TB, Arthur can nonetheless homicide actually dozens of armed opponents unimpeded.

Joel from The Final of Us, which involves PC in March, is one other instance, narratively a tortured everyman always fearful for his personal and Ellie’s survival, mechanically an unstoppable killer, spilling blood by the fluid ton. The answer nevertheless just isn’t at all times to keep away from violence in video games, or solely to moralise over it like a Spec Ops The Line or This Conflict of Mine.

Slightly, violence must be contextualised and significant, to someway have an effect on the character and the story. This impression and that means can nonetheless be joyful and rewarding – I assure that killing enemies in a videogame, when you understand who they’re, what they’ve finished, and what killing them means, can be extra gratifying even in a fundamental, primal manner than killing a bunch of fodder.

However the bodycount in shooters, not less than these with sure dramatic pretensions, wants to come back down, in any other case we’ll at all times be enjoying as unrelatable super-people, whose inside lives, regardless of how effectively constructed, will really feel terminally unfamiliar.